Java Thread Programming (Part 5)

- November 02, 2021

- 4435 Unique Views

- 5 min read

In our previous article, we discussed the "data race" concept and how we can solve it using volatile keywords. However, this is not the only problem we face when dealing with code that runs in multi-threaded environments. In this article, we will discuss another situation called "race conditions" and how we can resolve it.

By now, we know that threads share memory space so that multiple threads can read from and write to the same variable. Unfortunately, although this ability gives us faster memory access, it has an unpleasant side effect which we call "race condition," and it creates data inconsistency in the program. To understand the problem, let's see an example.

In the following code, we will try to simulate a bank account. We will keep debiting and crediting the same amount from two different threads from an account. The idea is, if we debit and credit the same amount multiple times, the net result should remain the same.

package com.bazlur;

public class BankAccount {

private long balance;

public BankAccount(long balance) {

this.balance = balance;

}

public void withdraw(long amount) {

long newBalance = this.balance - amount;

this.balance = newBalance;

}

public void deposit(long amount) {

long newBalance = this.balance + amount;

this.balance = newBalance;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.valueOf(balance);

}

}

The above class is a super simple Java class. It has two methods. One deposits an amount, and the other withdraws an amount from a bank account. The balance variable is that from where we do read the value from and write to.

Let’s use this class in a multi-threaded code.

Tangent: We started two threads from the main method. One main method starts the two threads, and then it dies. The other two threads keep running. We need to print the balance value once these two threads finish their work, and we can do that from the main method. The problem is that the main thread already died at this point. We can keep the main thread waiting until the other two threads die using

Thread.join()method call. Once both threads are finished, the main thread print the value and then exit.

In the above code, in the main method, we have created an instance of the BankAccount class with an initial balance, 100. Then we have created two threads, one does deposit, and the other one does withdraw. Both of them do this operation inside a loop, more precisely 1000 times.

The expectation is that if both threads run the code, the net result of the balance should remain the same as the initial balance.

Unfortunately, that’s not the case. When we run it, we get a different result each time. Sometimes it’s negative, and other times it’s positive, but not precisely to the initial balance.

Can we solve this problem by declaring the balance variable volatile? The answer is no. Volatile keywords solve the visibility problem, but the situation we are dealing with now isn’t that.

Let’s put our program into a symbol and pseudocode table-

| Thread 1 | Thread 2 |

|---|---|

| 1.1 L1 = S.X + 100 | 2.1 L2 = S.X- 100 |

| 1.2 S.X = L1 | 2.2 S.X = L2 |

So we have several execution orders here. However, only the following execution order would maintain the accuracy of the calculation.

Execution Order: 1.1, 1.2. 2.1, 2.2 Execution Order 2: 2.1, 2.2, 1.1, 1.2

But we can not guaranty that the execution order would only be the these two.

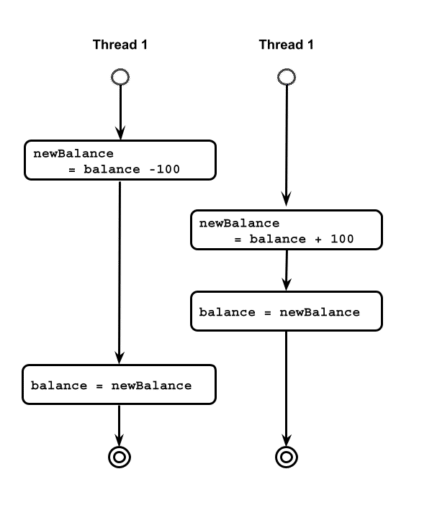

What if the execution order is the following:

Execution Oder: 1.1, 2.1, 2.2, 1.2

If the code is executed with the above order, the output will not be what we expect.

The variable balance is shared in both threads. When a thread changes/updates the variable, two things happen: it reads and then writes.

If a thread reads before another thread finishes its writing, that's where things go out of the way.

It starts with 1.1, after exacuting this line, the local variable becomes 100 + 100, which is 200. 2.1 starts immediately after it, so the first thread doesn’t get a chance to update the value to the balance variable yet. Line 2.1, the thread read the value from the balance variable, subtract 100 from it and keep the result in the local variable, which is now 0. 2.2 update the value to the balance variable. And then, when 1.2 executes, the local variable here is 200, and it updates the balance variable with it.

And this is how it produces an incorrect result.

The only way we can fix this problem is if the thread executes the write operation automatically. While it’s doing it, no other thread can read it until it finishes the operations.

The answer to the problem is, creating a mutual exclusion between the thread. Let me give you a practical example- When we go to the washroom, we lock the facilities so that one else can use it at the time. However, when one finishes using facilities, someone else can use it. The idea of a lock can be used here. When a thread reads and writes a shared variable, we have to guard that variable a lock so no other thread can access it before it unlocks it.

The area in the code that reads from and writes to a variable, called critical sections. If the code section doesn’t execute atomically, then there is a possibility of happening race condition. Race conditions can be prevented by keeping critical inside a synchronized block.

Achieving this mutual exclusion in Java is pretty straightforward. The trick is to use thesynchronized keyword with a lock object. For example, if we rewrite our BankAccount class as follows, then the problem will go away.

When a thread acquires the lock object, no other thread will be able to use this lock. Once a thread unlocks the lock, other threads than the original thread can acquire it again. That means the critical section of the code will now be executed automatically.

package com.bazlur;

public class BankAccount {

private long balance;

private final Object lock = new Object();

public BankAccount(long balance) {

this.balance = balance;

}

public void withdraw(long amount) {

synchronized (lock) {

System.out.println("Acquired Lock: " + Thread.currentThread());

long newBalance = this.balance - amount;

this.balance = newBalance;

System.out.println("Unlocked the lock: " + Thread.currentThread());

}

}

public synchronized void deposit(long amount) {

synchronized (lock) {

System.out.println("Acquired Lock: " + Thread.currentThread());

long newBalance = this.balance + amount;

this.balance = newBalance;

System.out.println("Unlocked the lock: " + Thread.currentThread());

}

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.valueOf(balance);

}

}

if you run the main method again, the output would be consistent.

The other way is that every Java object has an intrinsic lock in it. It is called "monitor lock" as well. If we add the synchronized keyword in the method signature, it uses the intrinsic lock. Example:

package com.bazlur;

public class Counter {

private int count;

public synchronized void increment() {

this.count = this.count + 1;

}

public int getCount() {

return count;

}

}

Now let’s summarize what we have just learned from this discussion and a few more essential notes:

- A variable is shared among multiple threads, and when one of them writes to the variable, then that’s a critical section.

- The critical section has to be guarded by a lock. Otherwise, a race condition will happen.

- We can use synchronized keywords. Any object can be used as a lock in Java. However, every object has an intrinsic lock or a monitor lock in it. If we use a synchronized keyword in the method signature, then the intrinsic lock is used.

- The synchronized block works as an atomic operation, even if it has more than one statement.

- If we use a synchronized block over a critical section, the shared variable does not need to use a volatile keyword. The synchronize keyword itself removes the visibility problem. That means the variable is always read from or written to main memory.

That’s all for today!

Don’t Forget to Share This Post!

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first.