Is it Time to go Back to the Monolith?

- March 03, 2023

- 7408 Unique Views

- 7 min read

History repeats itself. Everything old is new again and I’ve been around long enough to see ideas discarded, rediscovered and return triumphantly to overtake the fad.

In recent years SQL has made a tremendous comeback from the dead. We love relational databases all over again. I think the Monolith will have its space odyssey moment again. Microservices and serverless are trends pushed by the cloud vendors, designed to sell us more cloud computing resources.

Microservices make very little sense financially for most use cases. Yes, they can ramp down. But when they scale up, they pay the costs in dividends. The increased observability costs alone line the pockets of the “big cloud” vendors.

You can check out a video version of this post here:

I recently led a conference panel that covered the subject of microservices vs. monoliths. The consensus in the panel (even with the pro monolith person), was that monoliths don’t scale as well as microservices.

This is probably true for the monstrous monoliths of old that Amazon, eBay et al. replaced. Those were indeed huge code bases in which every modification was painful and their scaling was challenging. But that isn’t a fair comparison. Newer approaches usually beat the old approaches. But what if we build a monolith with newer tooling, would we get better scalability?

What would be the limitations and what does a modern monolith even look like?

Modulith

To get a sense of the latter part you can check out the Spring Modulith project. It’s a modular monolith that lets us build a monolith using dynamic isolated pieces. With this approach we can separate testing, development, documentation and dependencies. This helps with the isolated aspect of microservice development with little of the overhead involved. It removes the overhead of remote calls and the replication of functionality (storage, authentication, etc.).

The Spring Modulith isn’t based on Java platform modularization (Jigsaw). They enforce the separation during testing and in runtime, this is a regular Spring Boot project. It has some additional runtime capabilities for modular observability but it’s mostly an enforcer of “best practices”. This value of this separation goes beyond what we’re normally used to with microservices but also has some tradeoffs. Let’s give an example. A traditional Spring monolith would feature a layered architecture with packages like:

com.debugagent.myapp com.debugagent.myapp.services com.debugagent.myapp.db com.debugagent.myapp.rest

This is valuable since it can help us avoid dependencies between layers. E.g. the DB layer shouldn’t depend on the service layer. We can use modules like that and effectively force the dependency graph in one direction: downwards. But this doesn’t make much sense as we grow. Each layer will fill up with business logic classes and database complexities. With a Modulith, we’d have an architecture that looks more like this:

com.debugagent.myapp.customers com.debugagent.myapp.customers.services com.debugagent.myapp.customers.db com.debugagent.myapp.customers.rest com.debugagent.myapp.invoicing com.debugagent.myapp.invoicing.services com.debugagent.myapp.invoicing.db com.debugagent.myapp.invoicing.rest com.debugagent.myapp.hr com.debugagent.myapp.hr.services com.debugagent.myapp.hr.db com.debugagent.myapp.hr.rest

This looks pretty close to a proper microservice architecture. We separated all the pieces based on the business logic. Here the cross dependencies can be better contained and the teams can focus on their own isolated area without stepping on each other's toes. That’s a lot of the value of microservices without the overhead.

We can further enforce the separation deeply and declaratively using annotations. We can define which module uses which and force one-way dependencies. So the human resources module will have no relation to invoicing. Neither would the customers module. We can enforce a one-way relation between customers and invoicing and communicate back using events. Events within a Modulith are trivial, fast and transactional. They decouple dependencies between the modules without the hassle. This is possible to do with microservices but would be hard to enforce. Say invoicing needs to expose an interface to a different module. How do you prevent customers from using that interface?

With modules we can. Yes. A user can change the code and provide access, but this would need to go through code review and that would present its own problems. Notice that with modules we can still rely on common microservice staples such as feature-flags, messaging systems, etc. You can read more about the Spring Modulith in the docs and in Nicolas Fränkels blog.

Every dependency in a module system is mapped out and documented in code. The Spring implementation includes the ability to document everything automatically with handy up-to-date charts. You might think, dependencies are the reason for Terraform. Is that the right place for such “high level” design?

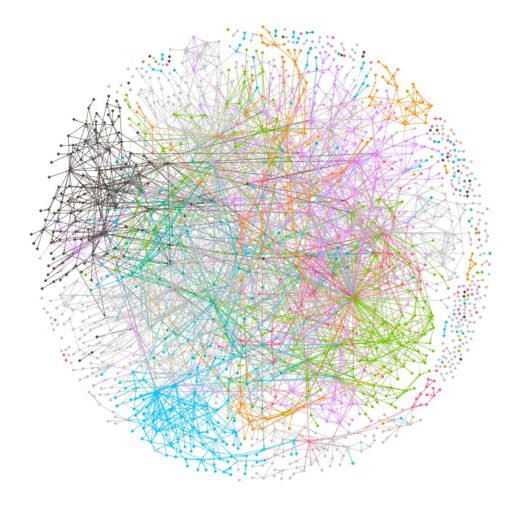

An Infrastructure as Code (IaC) solution like Terraform could still exist for a Modulith deployment. But they would be much simpler. The problem is the division of responsibilities. The complexity of the monolith doesn’t go away with microservices as you can see in the following image (taken from this thread). We just kicked that can of worms down to the DevOps team and made their lives harder. Worse, we didn’t give them the right tools to understand that complexity so they have to manage this from the outside.

That’s why infrastructure costs are rising in our industry, where traditionally prices should trend downwards… When the DevOps team runs into a problem they throw resources at it. This isn’t the right thing to do in all cases.

Other Modules

We can use Standard Java Platform Modules (Jigsaw) to build a Spring Boot application. This has the advantage of breaking down the application and a standard Java syntax. But it might be awkward sometimes. This would probably work best when working with external libraries or splitting some work into common tools.

Another option is the module system in maven. This system lets us break our build into multiple separate projects. This is a very convenient process that saves us from the hassle of enormous projects. Each project is self-contained and easy to work with. It can use its own build process. Then as we build the main project everything becomes a single monolith. In a way, this is what many of us really want…

What about Scale?

We can use most of the microservice scaling tools to scale our monoliths. A great deal of the research related to scaling and clustering was developed with monoliths in mind. It’s a simpler process since there’s only one moving part: the application. We replicate additional instances and observe them. There’s no individual service that’s failing. We have fine grained performance tools and everything works as a single unified release.

I would argue that scaling is simpler than the equivalent microservices. We can use profiling tools and get a reasonable approximation of bottlenecks. Our team can easily (and affordably) set up staging environments to run tests. We have a single view of the entire system and its dependencies. We can test an individual module in isolation and verify performance assumptions.

Tracing and observability tools are wonderful. But they also affect production and sometimes produce noise. When we try to follow through on a scaling bottleneck or a performance issue, they can send us down the wrong rabbit hole.

We can use Kubernetes with monoliths just as effectively as we can use it with Microservices. Image size would be larger but if we use tools like GraalVM, it might not be much larger. With this we can replicate the monolith across regions and provide the same fail-over behavior we have with microservices. Quite a few developers deploy monoliths to Lambdas, I’m not a fan of that approach as it can get very expensive. But it works...

The Bottleneck

But there’s still one point where a monolith hits a scaling wall: the database. Microservices achieve a great deal of scale thanks to the fact that they inherently have multiple separate databases. A monolith typically works with a single data store. That is often the real bottleneck of the application. There are ways to scale a modern DB. Clustering and distributed caching are powerful tools that let us reach levels of performance that would be very difficult to match within a microservice architecture.

There’s also no requirement for a single database within a monolith. It isn’t out of the ordinary to have an SQL database while using Redis for cache. But we can also use a separate database for time series or spatial data. We can use a separate database for performance as well, although in my experience this never happened. The advantages of keeping our data in the same database is tremendous.

The Benefits

The fact that we can complete a transaction without relying on “eventual consistency” is an amazing benefit. When we try to debug and replicate a distributed system, we might have an interim state that’s very hard to replicate locally or even understand fully from reviewing observability data.

The raw performance removes a lot of the network overhead. With properly tuned level 2 caching we can further remove 80-90% of the read IO. This is possible in a microservice but would be much harder to accomplish and probably won’t remove the overhead of the network calls.

As I mentioned before, the complexity of the application doesn’t go away in a microservice architecture. We just moved it to a different place. In my experience so far, this isn’t an improvement. We added many moving pieces into the mix and increased overall complexity. Returning to a smarter and simpler unified architecture makes more sense.

Why use Microservices

The choice of programming language is one of the first indicators of affinity to microservices. The rise of microservices correlates with the rise of Python and JavaScript. These two languages are great for small applications. Not so great for larger ones.

Kubernetes made scaling such deployments relatively easy, thus it added gasoline to the already growing trend. Microservices also have some capability of ramping up and down relatively quickly. This can control costs in a more fine grained way. In that regard microservices were sold to organizations as a way to reduce costs. This isn’t completely without merit. If the previous server deployment required powerful (expensive) servers this argument might hold some water. This might be true for cases where usage is extreme, a sudden very high load followed by no traffic. In these cases, resources might be acquired dynamically (cheaply) from hosted Kubernetes providers.

One of the main selling points for microservices is the logistics aspect. This lets individual agile teams solve small problems without fully understanding the “big picture”. The problem is, it enables a culture where each team does “its own thing”. This is especially problematic during downsizing where code rot sets in. Systems might still work for years but be effectively unmaintainable.

Start with Monolith, Why Leave?

One point of consensus in the panel was that we should always start with a monolith. It’s easier to build and we can break it down later if we choose to go with microservices. But why should we?

The complexities related to individual pieces of software make more sense as individual modules. Not as individual applications. The difference in resource usage and financial waste is tremendous. In this time of cutting down costs, why would people still choose to build microservices instead of a dynamic, modular monolith?

I think we have a lot to learn from both camps. Dogmatism is problematic as is a religious attachment to one approach. Microservices did wonders for Amazon. To be fair their cloud costs are covered…

On the other hand, the internet was built on monoliths. Most of them aren’t modular in any way. Both have techniques that apply universally. I think the right choice is to build a modular monolith with proper authentication infrastructure that we can leverage in the future if we want to switch to microservices.

Don’t Forget to Share This Post!

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first.