Java Thread Programming (Part 11)

- January 26, 2022

- 3247 Unique Views

- 4 min read

In the second article of this series, we saw that we can create a functional web server application using Java threads. With that, we could receive multiple requests from many clients and serve them properly.

However, there is a limitation. We cannot just receive an unbounded number of requests simultaneously. The constraint is not on the sockets. The modern OS can handle millions of open sockets at a time. That means, in theory, we should be able to serve that many requests at a time.

The limitation is that we cannot create an unbounded number of threads.

We did an experiment in the 7th article of the series and figured out that we cannot just have an unbounded number of threads in a machine.

Let’s do the same test again to determine how many threads we can create on a machine.

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger;

import java.util.concurrent.locks.LockSupport;

public class Playground {

public static void main(String[] args) {

var counter = new AtomicInteger();

while (true) {

new Thread(() -> {

int count = counter.incrementAndGet();

System.out.println("thread count = " + count);

LockSupport.park();

}).start();

}

}

}

The above program is a simple one. It creates threads in a loop and then parks them, which means the thread gets disabled for further use, but it certainly does the system call and allocates memory. It keeps creating threads until it cannot create anymore, throwing an exception, OutOfMemoryError. We are interested in the number we get until the program throws an exception.

On my machine, I was able to create only 2020 threads with the following configurations.

Chip: Apple M1 Memory 8GB OS: macOS Monterey

As you can see, we cannot create many threads as the request comes along. Also, spawning a new thread on each request is costly; it takes up memory and time to create a thread. If too many requests come to the server, and the response time between a request and response is shorter, then many threads will be created within a short window of time. And creating threads and stoping them, we will have to use CPU resources.

Besides, in a machine, we have a limited amount of CPUs, and at a point in time, a CPU can only handle one thread. That means, if we have 4 CPUs in a machine, we will have four threads running at a point in time, and the rest of them will be waiting.

As a result, the thread scheduler has to be super busy to provide a time slice to each. Therefore, having many threads means more context switching, which also has overhead. So eventually, it will result in degrading the performance of the application.

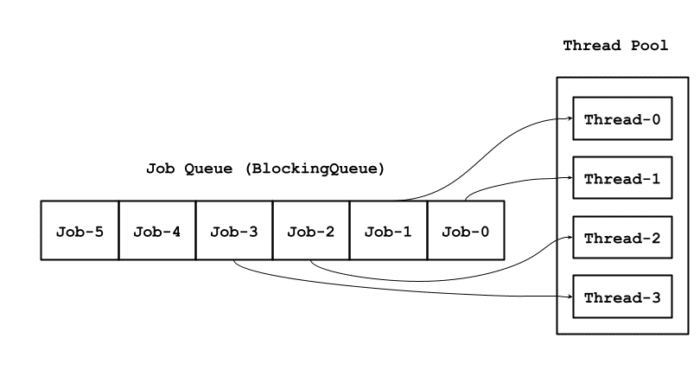

To solve all of the problems above, Java introduced a technique called, ThreadPool. In a ThreadPool, we will create several threads when the application starts (we can create on-demand as well), and they will be waiting in Queue; when a request comes into the server, a thread will be picked from the pool, and given the task to the thread, once the thread is done with the job, the thread will return to the pool. The idea is that we will have a limited number of threads, and we will reuse them.

In our 7th article of the series, we created a thread pool of our own, that wasn’t production-ready. However, in JDK, we have classes that help us to instantiate a production-ready thread pool. Let’s discuss that.

In Java, ThreadPool is realized through a framework called Executor. It has a special interface:

public interface Executor {

void execute(Runnable command);

}

This interface has only one method; execute () takes an instance of Runnable interface.

A request comes from a client ot a server, and the server responds. In between, the server does specific work. We can call it a unit of work or a job. We will pass that unit of work or job to the execute() method.

The executor framework underneath works as a producer/consumer pattern. The jobs we put in it are the producer, and the threads inside the executor framework are the consumer of the jobs.

This interface has several implementations. But to make it simple, we have a factory class named, Executors. It has many static factory methods, which makes our life easy.

Let’s see how we can use it:

import java.io.IOException;

import java.net.ServerSocket;

import java.net.Socket;

import java.util.concurrent.ExecutorService;

import java.util.concurrent.Executors;

public class MultiThreadedServer {

public static void main(String[] args) throws IOException {

ServerSocket serverSocket = new ServerSocket(8080);

ExecutorService threadPool = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(10);

while (true) {

Socket socket = serverSocket.accept();

threadPool.execute(new Runnable() {

@Override

public void run() {

handleRequest(socket);

}

});

}

}

private static void handleRequest(Socket socket) {

//Todo send the appropriate response to the client

}

}

The above program is a fully multithreaded web server, but we didn’t create any threads by ourselves. Instead, we created a thread pool using Executors. We specified the number of threads we required, and then the executors provided us with a thread pool with that number. Whenever we get a request from a client, we call a method, handleRequest(), to handle the request and send a response. We wrap the handleRequest() method in a runnable and submit it to the thread pool.

This is quite simple. We don’t have to create any threads manually, instead, at the startup of the application, we will ask the executor framework to provision threads for us, and they will be reused the whole time, as long as the application runs.

I hope this clears up the purpose of the executor framework, and in the following article, we will go a bit further in-depth about the framework. Till then, stay happy, and be curious!

Don’t Forget to Share This Post!

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first.