Java Thread Programming (Part 15)

- August 31, 2022

- 3472 Unique Views

- 4 min read

This article will discuss how we do asynchronous method invocation with Callable and Future with a practical example.

Look at the code snippet. It doesn’t have anything yet, but as we learned about Java threading, we know anything we put here will run on the main thread unless we spawn a new thread from here.

Now consider a case where you work as a banker, and you need to calculate how much credit you can provide to a person.

To calculate the credit, you need to calculate that person’s assets and liabilities. And then, you want to do some other tasks and pass the assets and liabilities to the credit score calculator. So let’s put these thoughts into code:

private static Credit calculateCreditForPerson(Long personId) {

var person = getPerson(personId);

var assets = getAssets(person);

var liabilities = getLiabilities(person);

doSomeImportantTask();

return calculateCredit(assets, liabilities);

}

This is pretty sequential, and all of them are done one after one. Each method takes some time to work on. It calls the database and then waits for the result. Until the result is returned, the execution waits. This is a blocking scenario.

That means when it calls the getPerson() method, if it makes a network call, which is usually an IO-bound task until we get the result, the main thread would just block, and nothing would progress here. Once the result is returned, we get to the next method, which is another blocking method, as it also makes a database call over the network.

We have five methods over here. If all of them take around 200 milliseconds each to execute, that’s 1000 milliseconds. While executing all the methods, the main thread is blocked most of the time without doing anything. We shouldn’t really waste a resource like this. How about we optimize it so that it doesn’t take the whole 1000 milliseconds?

The solution is to pass those method executions into different threads. Of course, we can create a new thread for each method directly through the new operator, but we need to get the result from the thread.

AtomicReference person = new AtomicReference<>();

new Thread(() -> {

var p = getPerson(personId);

person.set(p);

}).start();

We could do something like the above. We are essentially sharing the state between the main and newly created threads. In such a case, we use AtomicReference to update variables in a thread-safe way.

But over here, we are spawning a new thread. So each time we execute the code, we have to create multiple threads. Creating threads is an expensive operation. We should not create them on an ad-hoc basis. We should use ThreadPool instead, which we will do later. Let’s see the whole code.

private static Credit calculateCreditForPerson(Long personId) throws InterruptedException {

var person = getPerson(personId);

var assetRef = new AtomicReference();

var t1 = new Thread(() -> assetRef.set(getAssets(person)));

var liabilitiesRef = new AtomicReference();

var t2 = new Thread(() -> liabilitiesRef.set(getLiabilities(person)));

var t3 = new Thread(() -> doSomeImportantTask());

t3.start();

t1.join();

t2.join();

var credit = calculateCredit(assetRef.get(), liabilitiesRef.get());

t3.join();

return credit;

}

Over there, the first method call is indeed a blocking call. The main thread waits for the method to finish the work. The following two methods' invocation depends on this, so even if we execute it through another thread, we need to wait for its results.

So executing it from the main thread makes sense. The next three methods can be executed independently. They should not wait for each other. So we can pass them into three separate threads, which we did over here.

The final method of invocation is dependent on the second and third methods. So we need to wait on them. That's why we called the join method on the threads of those two methods.

And finally, before returning the credit, we join the third thread.

The code above works and takes less time, but it is very hard to understand and has too many moving parts.

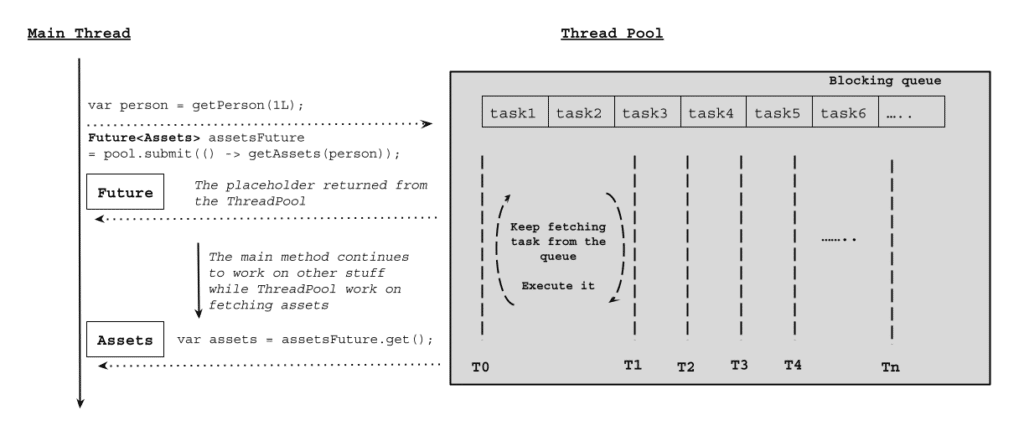

Let’s not create a thread for each method by ourselves; rather, we should use executors. That’s best practice. Let’s do that.

private static Credit calculateCreditForPerson3(ExecutorService pool)

throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

var person = getPerson(1L);

Future<Assets> assetFuture = pool.submit(() -> getAssets(person));

Future<Liabilities> liabilitiesFuture = pool.submit(() -> getLiabilities(person));

pool.submit(() -> doSomeImportantTask());

return calculateCredit(assetFuture.get(), liabilitiesFuture.get());

}

To know how the future works, read part 12 of this threading series: https://foojay.io/today/java-thread-programming-part-12/.

The code exactly does the same thing, but it is much cleaner and better. The basic idea is that the second and third methods are being executed independently and separately in other threads.

While they are being executed, the main thread is not blocked, and we made some progress in invoking the fourth method. Indeed, when we called future.get() blocking call the final method, but that is necessary. It could happen that they are already finished when we get to the final method.

While the final method is executed in the main thread, the fourth method is being executed in another thread asynchronously.

So we have learned how we can write asynchronous methods using Executors, Callable and Future.

CompletableFuture is another way to deal with asynchronicity in Java, and it is considered to be a much better way. This is how the above code can be written:

private static Credit calculateCreditForPerson(Long personId) throws ExecutionException, InterruptedException {

return CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> getPerson(personId))

.thenComposeAsync(person -> {

final var assetFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> getAssets(person));

final var liabilitiesFuture = CompletableFuture.supplyAsync(() -> getLiabilities(person));

final var importantWork = CompletableFuture.runAsync(Playground::doSomeImportantTask);

return importantWork.thenCompose((v) -> assetFuture.thenCombineAsync(liabilitiesFuture, ((assets, liabilities) -> calculateCredit(assets, liabilities))));

}).get();

}

But I wouldn't explain this in this article because it needs some background. Please wait until the next parts come out...

Until then, cheers!

Don’t Forget to Share This Post!

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first.